By April Brown

A few years ago, I was eating dinner with a colleague at a restaurant in Seattle after a long day of filming (we don’t actually use film anymore) for the PBS NewsHour. A few tables away, I saw what appeared to be three generations of a family—a grandfather, parents and a couple of kids. All of them were looking at what appeared to be their smartphones. Minutes passed before anyone spoke. I looked over periodically throughout our meal, and there was always at least one person looking down at his or her phone.

That situation wasn’t entirely surprising. After all, most of us are in some way attached to a smartphone, and I’ve read reports about the effect they’re having on our personal relationships. After the first few weeks of my first semester teaching full-time at a university, I am nearly ready to conclude they are affecting my relationships with students.

My evidence is anecdotal, but it seems to me that with all the time students spend interacting with people remotely and some ways impersonally, many of them have a hard time with the personal communication. Specifically, there is a serious lack of listening going on.

It’s not just the distractions they bring to class in a shiny aluminum case, it’s the years of training in piecemeal communication without a visual connection to another person. The “short attention span theater” phenomenon (not to be confused with the former Comedy Central clip show of the same name) has been amplified, according to a Yale graphic design critic, leading to “multimedia multitasking” and skimming.

I do remember, vaguely, what it was like to be in a class I wasn’t fully engaged in (which, for the record, was well before smartphones.) And while it is my responsibility to try to keep students interested, there is another side to that coin. If they’re not aurally present, it may not matter.

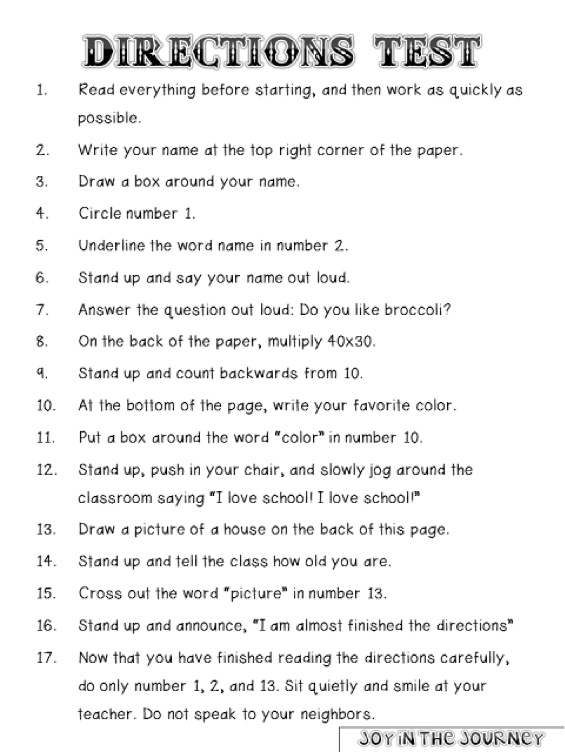

It has been as evident when I give basic instructions (“write your name and class number on your paper”) as it is when I talk about something they may consider more critical to their success (“you will be given a failing grade if you do not …”). I’ve even been debating whether to use an elementary school “follow the directions” test a colleague recommended just so they understand the concept.

A smartphone-awareness class might be a useful addition to the curriculum, or a lesson at the very least. I may need to start being specific about how and when phones can be useful in class—not for texting— for perhaps for double-checking facts or looking up supplemental information. But thus far, smartphones in class have not been the largest problem.

The problem is this: If students are not listening to the information that is given, they can’t possibly be able to think critically about it.

It may be a student’s right not to pay attention or follow directions, but my students shouldn’t expect to do well in my class if they don’t.

April Brown is an Assistant Professor of journalism at Northern Arizona University. She has an M.A. in International Broadcast Journalism and is an award-winning journalist and Special Correspondent for the PBS NewsHour. She has also worked for the BBC and ITN based in London, and as freelance producer for ABC News and NBC News in the United States.